Questrade Revisited: Clarifications . . . and Dangerous Loopholes

By: Jason Periera Editor & Contributor: Alexandra Macqueen

Addressing questions and statements that came from my first critique of Questrade’s marketing.

Key Takeaways

My first Questrade article met with several misunderstandings and challenges.

The question of how Questrade could advertise up to 30% richer leads to a sad conclusion that they can because it’s permitted.

Questrade’s may have unlocked pandora’s box by showing the industry that undeliverable promises are fair play.

A few weeks ago, I published a critique of Questrade’s marketing and brand promise. As the post gained traction, several people publicly commented both in support and opposition to the article, and many more reached out privately.

While the resulting discussion included many positive conversations – and debates around more nuanced points – there were also some misunderstandings about the intent of my original post, and some questions that, in my view, necessitate further elaboration.

Hence, this follow-up post.

Clearing The Air

Too often people don’t bother to read anything beyond the headlines – so let’s clear the air for those who either didn’t fully read my work last time or just doubt my claims.

“If you hate Questrade, you must see them as a threat”

My opening line in the original post said that Questrade is almost universally hated in the financial advisor community in Canada. In response, some people pointed out that Questrade saves money for investors, concluding that clearly, I – or my livelihood – must be threatened (by this “good company” that does “good things” for Canadian investors).

Newsflash: of course most advisors hate – or at least are irked by – Questrade.

While Questrade started out by targeting “do-nothing” advisors, they’ve since shifted their marketing strategy to targeting all advisors and denying we provide any value whatsoever in what I think is an overly smug fashion as demonstrated by this one.

The question I have in response is “how could Questrade expect anything but near-universal contempt in the advisor community?” It seems some people can’t envision a situation where one disagrees with the position taken by another even if not personally adversely affected.

But to tell the potentially mind-bending truth: I don’t actually hate Questrade. In fact, I recognize the need for and support good low-cost investing options for Canadians – and I strongly support initiatives to dislodge poorly-served consumers from the “do-nothing” advisors who overcharge them.

What I do take issue with is Questrade’s tactics: making brand promises that can’t be delivered, denying the existence of advisor value, and shifting their marketing from targeting do-nothings to targeting all advisors.

If anything I’m arguing for Questrade to just be more honest. In fact, my colleague, friend, and advisor advocate John Degoey offered to connect me with the Questrade CEO, and I’d welcome the discussion. While I haven’t heard back yet, the door remains open.

“You’re just afraid of robos!”

I heard this claim several times: apparently, if I take issue with a company's actions, that must be because I’m “threatened.”

This claim is actually somewhat laughable, as my support and defence of Wealthsimple is on the record – and I’ve interviewed and count people at Nest Wealth, Wealthbar (now CI Direct Investing) and Wealthsimple as friends and colleagues, and have even worked with Wealthsimple for Advisors.

I’ll be sure to confess my fears to these friends directly when we next meet for drinks.

Don’t put words in my mouth

One message I got reminded me that no matter what you write, someone will always take your point too far. This is exactly what happened when an advisor contacted me to claim that his clients pay fees approaching 4% with total disclosure and are “more than happy.”

Let’s be clear: My article was absolutely not meant as carte blanche to justify any fee imaginable, whether 4%, 5%, or any other number.

In my post, I was careful to say that fees matter, but so does what you get in return – service and planning. Fees and the service clients get are two sides of the same coin: reasonable fees should be paired with good service in order for advisors to do right for their clients.

But I have a REALLY hard time imagining a scenario where an ongoing fee of 4% can be justified. Short of someone having an incredibly complex personal situation relative to their investable assets, or their market invested assets constitute a minority of their net worth, I can’t see how this math ends up working. One thing is for sure if we're talking 4% charged to the average RRSP investor with moderate-income for basic service, 4% is WAY off base given the alternatives in the marketplace.

Cutting the Crap on Marketing

One of the more nuanced debates I had in response to the original post was with Dale Roberts, of the Cut The Crap Investing Blog. Dale addressed my blog post with one of his own: “Retire Up To 30% Wealthier.” In his post, Dale raised a few points and questions that I think need some clarification. Here are Dale’s points and my responses:

1 - “Questwealth Portfolios – the robo offering from Questrade – come with advice, so it’s not an apples-to-apples comparison.”

Sure. But my response to that is: Define “advice.”

Let me start by defining the first two categories of “advice” in what I consider “the spectrum of advice.”

In my mind, “Do Nothing” advisors constitute a zero on a 0–10 scale of service. We can define these as advisors who point to a certain mutual fund, collect a DSC or 1% trail, and then do nothing to earn it beyond making a sale. Frankly, this to me does not constitute advice, hence the rating of zero, and to be clear: No one should EVER be paying for this service. This is the type of advisor that gives the entire industry a bad name.

What Dale is referring to is what I would term the level 1 on the advice scale: The Lowest Common Denominator (LCD) of Advice. I define LCD advice as service from a call-centre staffer to obtain ad hoc answers from someone who doesn’t know you or your personal situation. This is incredibly limiting as the advice and planning can only be given in general terms that may or may not match up fully with the fact pattern of the client’s life. While that’s arguably better than nothing (although it could actually be worse), this constitutes “advice” in the same way that McDonald’s is food. It’s (usually) better than nothing, and definitely better than working with a do-nothing advisor, and in my opinion, is priced fairly at 0.25%. Frankly, this is a fantastic option for many.

In the general, online conversation about advice the term is being thrown around like it’s a well-understood commodity, when in fact, financial advice is a highly differentiated service, ranging from a LCD call-centre response about whether a new graduate starting their first job should open a TFSA or RRSP, to comprehensive financial planning and full execution of that plan (which constitute about an 8 in my opinion) to the dedicated family office model for the ultra-wealthy (what I consider to be 10 on the spectrum), and all the countless points in between. Saying that “a robo provides advice” fails to acknowledge the fact that there are many differentiated segments to the overall financial advice market.

If your robo-advisor provides financial planning from qualified Certified Financial Planner® certificants, great. But as someone who knows people running these companies, this advice offering was only ever meant to serve the mass market on a one-off basis at best and the client-to-advisor ratios support that assertion.

When my clients call, in contrast, I know who they are, who their family is, their occupation, situation, what I have done for them and am doing for them, and even what we joke about frequently, all without looking them up. I can do that because my model is designed to provide high-touch and professionalism to a small number of households as I argued for in my Globe Advisor article “Why Advisors Need to Serve Fewer Clients.”

But do I consider my level of advice to be the level required by everyone, all the time?

No.

The market for financial advice is varied and the service I offer cannot be efficiently delivered to a new grad who is starting out (nor would they require the high-touch service I provide).

And while I have argued for lower overhead models that would permit advisors to deliver similar services for more modest portfolios, and I’m fully supportive of fee-only and subscription or subscription or retainer-based models (again, friends with many people following and advancing these models), there will always be a subset of Canadians who can’t afford to pay for any planning (as well as those who can’t invest at all).

That’s why I am appreciative that robos offering advisory services exist, as do a number of fledgling pro bono initiatives. But let’s call a spade a spade: Robos offer the bare minimum level of advice that one should accept and consider paying for.

Is it so hard to fathom that many people would be willing to pay for or have need of services that cost three or even six times the robo-advisor fee? (If not, then explain the sale of any car priced over $30,000 to me.)

2 - “Careful with your benchmarks.”

In my original post, I compared Questwealth returns to F-Class mutual funds available in the Canadian market. (F-class funds are sold without advice, which is provided and charged separately by the advisor.) The results were pretty “ugly,” with none of the Questwealth portfolios delivering top-quartile returns, and most of them significantly below that.

Here, I didn’t account for the fact that the Questwealth portfolios include an advice offering so, to Dale’s point, my comparison was off.

Questwealth’s management fee is 0.25%. The total cost of a Questwealth portfolio is the management fee of 0.25%, plus the management fee for the ETFs held in the portfolio.

So, in efforts to make a fairer comparison, I added back in the 0.25% to the Questwealth returns, in order to try and calculate a “pre-advice” return. My goal was to disprove the “30% more” brand promise by demonstrating that one cannot make promises on portfolio returns vs all other options, due to the number of variables at play. In order to make this comparison fair, one would have to look at the cost of investing in the portfolio only.

However, adding back in the 0.25% doesn’t make the results any less ugly. In fact, here are the most up-to-date five-year numbers from Morningstar (for the five years ending July 31, 2020) for the Questwealth portfolios in their respective categories, if 0.25% points are added to the original five-year returns:

Conservative (2.50% +0.25%): 76th out of 109 – 3rd Quartile

Income (3.03% +0.25%): 114th out of 162 – 3rd Quartile

Balanced (3.25% +0.25%): 285th out of 376 – 4th Quartile

Growth (3.52% +0.25%): 195th out of 266 – 3rd Quartile

Aggressive (3.83% +0.25%): 300th out of 416 – 3rd Quartile

Once again, no top-quartile rankings . . . and not even second-quartile showings. Instead, the results are split between third- and fourth-quartile rankings.

The true irony here is that despite adding back the 0.25% fee, the up-to-date rankings are actually worse (for the period of five years ending in July 2020, not April 2020) than in my original post.

3 - “A 30-second commercial can’t even begin to paint the full picture.”

True, but I don’t accept that excuse when it comes to making brand promises that have to do with people’s life savings, especially when they take 30 years to validate. If the 30-second format only allows you to paint broad strokes, you had better be sure they aren’t misleading.

This kind of stance – “Retire up to 30% wealthier” – is the thin edge of the wedge that can be used to rationalize any number of other bad brand promises (as I will soon demonstrate). When it comes to people’s life savings and lives, in my opinion, the financial services industry should be held to a far higher standard.

The Big Question

The thing that’s stuck with me through this entire process – writing the first article, discussing and debating that article, and now researching this one – is the simple question of “how is Questrade able to make the claim that by using their services, someone could retire 30% richer?”

Some advisors even privately lamented to me that they wish they could get similar claims past their compliance department.

So that left me wondering: How does Questrade “get away with it?”

I set off to find out, speaking to experts in several different fields. The answer to this question surprised me more than once.

The Lawyer’s View

My first stop was to speak to someone people turn to when the financial industry fails them: Harold Geller.

Harold is an Ottawa-based lawyer who is well known for helping clients sue their advisors when they fail them. It may surprise many people to know that Harold is not “anti-advisor” – instead, he actually sees the value of planning and advice. In his professional career, he’s seen everything – from competent professionals to the worst the industry has to offer.

His view on how Questrade is able to get away with their 30% claim is two-fold: one part lax enforcement and one part regulation that doesn’t specifically prohibit such claims. The result? Anyone can say pretty much anything, with very little fear of repercussions. In fact, Harold stated that were he ever to take Questrade to court, he would be using the 30% promise as a tool when arguing failure to deliver.

When asked if such a promise (presuming it was not delivered) would be grounds for a class-action lawsuit, he confirmed that in the US it absolutely would be – but in Ontario, it likely wouldn’t be, not because it would be without merit, but because legal changes have made class actions very difficult to certify.

The Marketer’s View

Next, I spoke with my friend David Pullara, an experienced consultant, business-school instructor, and marketer who has worked with consumer-centric Fortune-500 firms like Starbucks, Coca-Cola, and Google. His take on Questtrade’s marketing is that while the company may not be doing anything illegal, they certainly aren’t being as transparent as a company, particularly a financial institution the people rely on to protect their savings, should be.

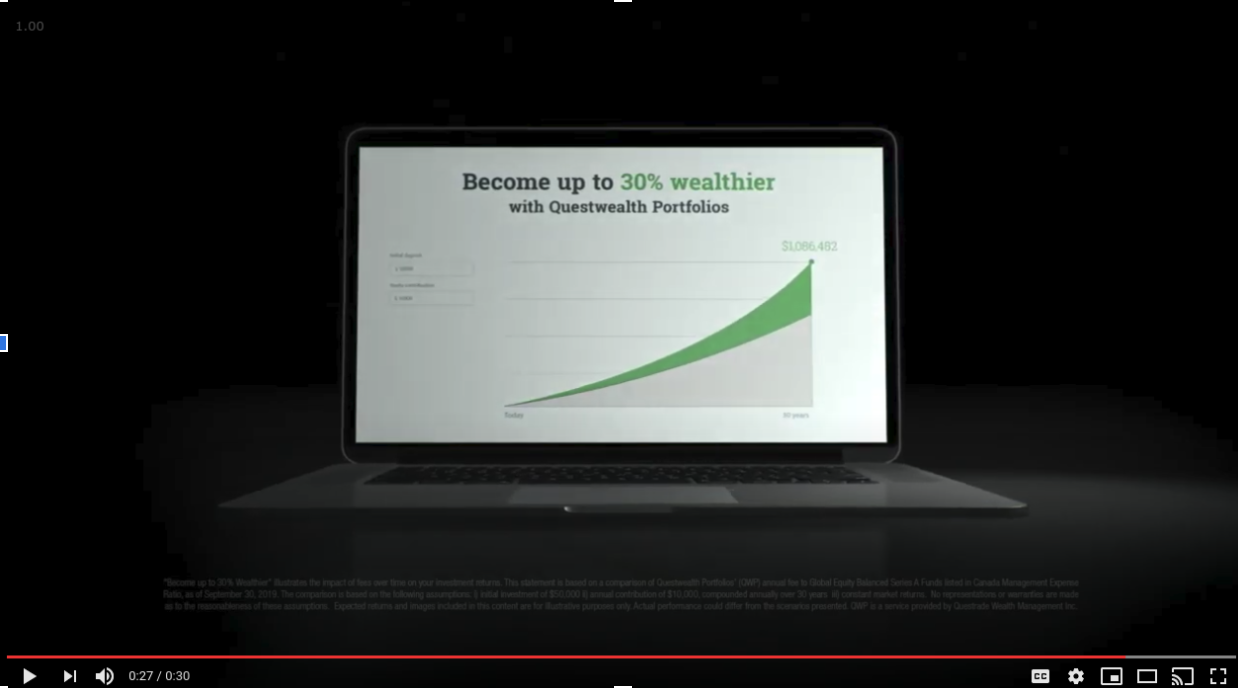

“Let’s be clear, Questtrade isn’t doing anything illegal with their marketing; they include a paragraph in their ad with all the assumptions they use to arrive at their ‘Become up to 30% wealthier’ claim, and using the words “up to” provides them with a lot of leeway. But that doesn’t mean what they’re doing is right.”

Pullara captured a screenshot of Questtrade’s January 2020 ad to illustrate his point.

“Have a look at the disclaimer paragraph from one of their recent ads: the font is tiny, and it’s grey text on a black background that appears for literally 2 seconds near the very end of a 30-second ad. Sure, the disclaimer is there, but realistically, are people going to read it? Of course not… and Questtrade knows that. They want you to pay attention to the “Become up to 30% wealthier” and hope you’ll ignore the many assumptions that go into that claim. That’s compliant with the law, and even adheres to a strict interpretation of the CMA’s code of ethics… but I think marketers shouldn’t be striving for the bare minimum when it comes to compliance, transparency, and truthfulness.”

Pullara is referring to the Canadian Marketing Association’s Code of Ethics and Standards, which has a standard on “Truthfulness” that reads: “Marketing communications must not omit material facts and must be clear, comprehensible and truthful. Marketers must not knowingly make a representation to a consumer or business that is false or misleading.” Questtrade’s disclaimer is comprehensible and truthful, although “clear” and “misleading” are up for debate.

Perhaps the CMA’s Code should require marketers to deal with the probability of occurrence whenever companies want to say that something could happen. After all, lottery corporations will often make “you could win” claims versus saying, “the odds of you winning the jackpot are so infinitesimal that you're more likely to get hit by a meteor”... but they publish the probabilities of winning on the back of every ticket sold.

Questrade’s claims of a deterministic outcome without providing for a range of probabilistic outcomes is at the core of my issue with the claim.

The Competition Bureau Loophole

Next, I turn to the government. The Competition Bureau of Canada regulates standards in advertising, including those surrounding representations of performance – and here I think I found another loophole.

The Competition Bureau’s regulations explicitly state that performance claims must be tested and that “the test should indicate that the result claimed is not a mere chance or one-time effect.”

These regulations were clearly written in the context of the physical realm, and not more intangible concepts like investment returns. The basis of Questrade’s claim was return = x. We take less off (in fees) than the other guy, so, therefore, x compounding over thirty years must = 30% more. Not exactly the most scientifically accurate argument.

The Chief Compliance Officer’s Surprise Response

On more than one occasion I have called up my chief compliance officer (CCO) with questions that no one else seems to ever ask, so he wasn’t surprised when I came to him with yet another.

This time, I contacted him with a marketing idea that would use Questrade’s logic against them. I told him that I wanted to run a thirty-year projection showing how I could beat Questrade’s performance by incorporating various value-adds I provide that have been quantified by the likes of Vanguard’s Advisor Alpha, Envestnest’s Capital Sigma, Morningstar’s Gamma, Cirano’s Gamma, and Russel’s Value of Advice, and that boost the returns my client’s experience.

Now to be clear, I don’t actually want to do this, nor am I advocating that anyone else does, this was just an experiment to see what compliance’s response would be. So I asked and awaited the “(sigh) Jason, why do you bother me with this nonsense” retort.

It never came.

Instead, I was told that if I could put together a marketing piece whose claims could be backed up by publicly available information, that they would be hard-pressed to stop me from using it. While one cannot lead clients to believe they are guaranteed a certain level of return or make false or exaggerated claims about investment performance, generalized statements not making promises yet grounded in evidence were fair play.

My response can best be summarized in a series of emoji:

So technically, in theory, I can take one or more of those studies, and tack on up to multiple percentage points to the Questrade performance illustrations, and then claim that if someone invested with me they could retire up to X% richer than Questrade a robo advisor! (note: compliance informed me that calling out Questrade as a basis for comparison was too close to a guarantee, but painting all robos with one brush, like Questrade does with advisors, is okay 🤷♂️)

Questrade may have unknowingly opened Pandora’s box.

The Comparison NO ONE Should Ever Claim

How would these numbers work out?

Let's use Questrade’s numbers comparison on a balanced portfolio as a baseline:

Assume ROR: 4.75%

Questwealth portfolio fee (higher-end): 0.41%

Questwealth Return: 4.34%

Average Mutual Fund Fee: 2.16%

Advisor Return: 2.59%

Let’s assume the average mutual fund fee would be the fee charged by the do-nothing advisor.

(Side note: Notice again how Questrade straw manned the comparison? There is nothing stopping an advisor from using the same ETFs as the Questwealth portfolio. Assuming they charged 1%+HST for services this would drop the fee from 2.16% to 1.26%, a 41% drop!)

As for the new portfolio, I will make the following assumptions:

I used the same ETFs as Questrade or its equivalent at the same cost, making the fee 0.15%.

I charge 1% as an advisor fee + HST = 1.13%

Then we will layer several value-adds from the various studies, specifically focusing on those not provided by Questwealth portfolios.

Drawdown/Spending strategy (Vanguard): +0.46%

Behavioural Coaching (Vanguard): +1.50%

Financial Planning (Envestnet): +0.50% (lower threshold)

Tax Management (Envestnet): +1.00%

Total Wealth Allocation (Morningstar): +0.45%

Annuity Allocation (Morningstar): +0.10%

Liability-Relative Optimization (Morningstar): +0.12%

Together, the value of all of these value-adds is 4.13%.

I stopped there as it was getting a wee bit nuts. Total value-add: 4.13%, making the total return I COULD technically project at:

4.75% (return) minus 0.15% (ETF MER) minus 1.13% (cost of advice + HST) plus 4.13% (added value from value-adds) = 7.6%

That would make the final tally over 30 years:

Do-nothing advisor: 115.35%

Questrade Robo: 257.70% (123.4% more than the do-nothing advisor)

Me: 800.26% (593.77% more than the do-nothing advisor, and 210.54% more than Questrade)

So TECHNICALLY, I could potentially claim that I could deliver double what a Robo does over thirty years and still be in line with regulations.

Does everyone see the problem here?

No, not the validity of some of the value-add claims, which I do question, but the concept of the comparison at all.

At its core neither I, nor Questrade, nor ANYONE AT ALL should be making claims like this – as they are unverifiable, unmeasurable and ultimately, undeliverable. We cannot guarantee any part of this equation: returns, fees, HST, or full delivery of the value-adds. None of us can predict the future, nevermind make quantifiable promises about that future!

The Box is Now Open

I am avid listener of Dan Carlin’s various podcasts, Hardcore History and Common Sense, the latter of which is a political commentary podcast.

From Carlin, I learned that when Obama was the US president he mused about what he felt was a troubling increase in use of Presidential Executive Orders to pass policy by circumventing Congress.

His musings would often meet with resistance from his generally left-leaning followers – to which Obama’s response was “just remember, you may be okay with it because it's your guy signing into law things you agree with, but what happens when it’s not your guy and you don’t agree with it?”

Needless to say, based on the last four years, I am guessing that those same listeners now understand the dangers of precedent.

Here’s the connection to my argument: While DIY and low-cost advocates defended the 30% brand promise to me, they failed to see that not only was the logic flawed but also a troubling example of what others could do with the same logic. They couldn’t see it because, to them, their side was winning. Hopefully, this post makes them reconsider.

I went looking to answer the question of why Questrade could make their marketing claims and advisors could not.

Shockingly, and disappointingly, I found not only could they make said claims, but there was nothing stopping advisors from making similar claims.

In the end, Questrade’s ad campaign may have opened a Pandora’s box of BS claims by exposing the lack of regulation on this point. My hope is that compliance officers make their advisors keep to a higher standard – and that regulators eventually wake up to such a loophole as servicing no one other than the makers of undeliverable promises.

A few weeks ago, I published a critique of Questrade’s marketing and brand promise. As the post gained traction, several people publicly commented both in support and opposition to the article, and many more reached out privately.